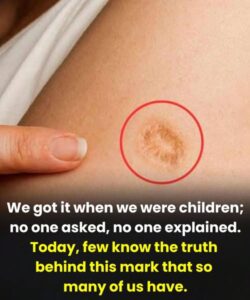

The small, round scar often found on the upper arm is frequently misidentified as a childhood injury or skin condition, but it is actually the result of the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, used to protect against tuberculosis (TB). Unlike modern intradermal injections, the BCG vaccine utilizes a weakened strain of Mycobacterium bovis, which triggers a deliberate, localized immune response. This process often involves the formation of a small blister or ulcer at the injection site that heals into a permanent, sunken scar. This mark is a biological record of the body’s natural defense mechanism, representing a successful encounter between the immune system and the vaccine rather than a medical failure or an untreated wound.

A persistent misconception suggests that the presence of this scar is a sign of poverty or a lack of modern healthcare, but the reality is rooted in global public health policy. In the 20th and 21st centuries, many countries with high tuberculosis burdens—regardless of their wealth or industrial status—implemented universal BCG immunization programs to protect infants. Because TB was once a global threat, millions of people across diverse social classes in Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe carry this mark. It is a reflection of geographic and historical health strategies rather than an individual’s hygiene, education, or socio-economic background.

There is also a common belief that the absence of a scar indicates a lack of vaccination or a failed immune response, but skin physiology varies significantly from person to person. While the scar is a common byproduct, some individuals heal with minimal to no visible marking, despite having a fully primed immune system. Conversely, the size or depth of the scar is not a direct metric for the strength of a person’s immunity against tuberculosis. Diagnostic clinical tests, such as the Mantoux tuberculin skin test, are far more accurate indicators of protection than the presence of a cutaneous mark, which can often fade or never form depending on the individual’s unique healing process.

Finally, it is essential to understand that the BCG scar is entirely benign and poses no threat to long-term health or immune stability. It is not a sign of a “damaged” immune system; rather, some researchers suggest that the “trained immunity” provided by the BCG vaccine can actually enhance the body’s ability to fight off other unrelated infections. The scar does not grow or spread, and while it may be a source of cosmetic concern for some, it remains a symbol of preventive medicine and early childhood protection. Understanding its origin helps to dismantle the unnecessary shame associated with the mark, transforming it from a mysterious blemish into a quiet story of global health and resilience.